Boom-and-Bust vs. Brick-and-Mortar

Why confusing “organizing” with “mobilizing” keeps us sprinting in circles.

Progressive politics loves a buzzword. We cycle through them, “relational organizing,” “digital mobilization,” “distributed everything”, as fast as they trend on X. The problem isn’t catchy language; it’s what gets lost inside the slogan. When a group brags that it “organized 10,000 people on Saturday,” odds are they didn’t organize at all. They mobilized a pre-existing list for a one-off action. Treating those two verbs as interchangeable isn’t just sloppy copy; it’s a strategic blind spot. We end up pouring resources into turnout spikes that evaporate by Monday and starving the slower, sturdier work that actually shifts power.

So let’s pump the brakes, untangle the wires, and say plainly what each mode delivers, and what it never will.

With the definitions clear, we can start treating mobilizing and organizing as complementary tools, each essential, each insufficient on its own, rather than tossing every tactic into one grab-bag called “organizing.” In the pages that follow, we’ll dig into how to use both with discipline, joy, and the rigor our moment demands.

For years, I’ve heard organizations scream, “We organized 10,000 people last weekend.”

Let’s be exact about what happened. They mobilized 10,000 supporters, tapped an email list, blasted a few texts, and convinced a ready-made base to show up for a march, a canvass launch, or a phone-bank marathon. That’s real work. But it is not the painstaking discipline of organizing: the slow, sweaty layering of relationships, leadership pipelines, and decision-making structures that let ordinary people keep contesting for power long after the sound system is packed into the van.

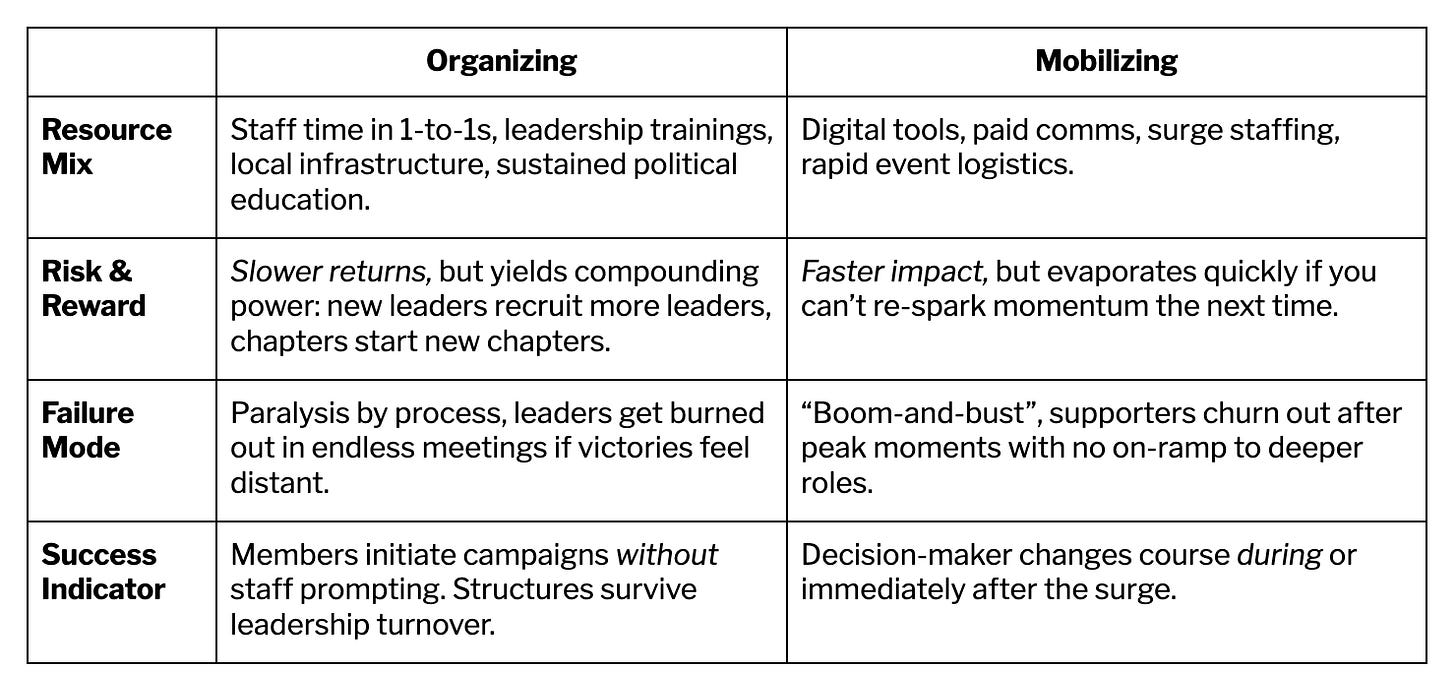

Why obsess over the distinction? Because each path forces different strategic investments:

Think of it as durability versus velocity:

Organizing bets that dense connective tissue, chapters, committees, crews, will hold when the next storm hits, whether that storm is a union-busting CEO or an authoritarian White House.

Mobilizing bets that if we flood the field with enough bodies and noise, we can tip a decision before the clock hits zero.

In reality, neither bet can cash out alone. Durable structures without rapid surges become insular; rapid surges without structures dissolve into nostalgia merch (“Remember that march?”). The tragedy is how often we collapse the two into a single hashtag, overfund the flashy spike, underfund the quiet scaffolding, and wake up to find our people both exhausted and politically brittle.

The takeaway for strategists: budget, staff, and measure separately for each mode, then design the hand-off so today’s marchers have tomorrow’s meeting to attend, and tomorrow’s leaders have yesterday’s list to activate. That’s the cycle that turns a moment into a movement.

WHAT MOBILIZING ACTUALLY DOES

Mobilizing begins with a countdown clock. Early vote opens in fourteen days. The zoning commission votes Thursday night. The state Senate will gavel in for a final vote at 9 a.m. sharp.

The assignment is simple and brutal: convert latent sympathy into visible pressure before the clock hits zero. Lists matter more than deep relationships, message discipline more than philosophical depth, and friction-free tech beats Robert’s Rules every time.

When it fires on all cylinders, mobilizing feels electric. Picture Georgia’s January 2021 runoff sprint: millions of calls, door knocks, and WhatsApp nudges drum-tight around a single date. Every night the data team posted pacing numbers; every morning the field adjusted in real time. Volunteers left sweaty, exhilarated, and, most important, immediately invited into something bigger the next day.

When it misfires, mobilizing turns into a live-action spam folder. URGENT! blasts hit anyone who once donated five dollars; petitions disappear into an unmanned Dropbox; volunteers who dialed a hundred strangers hear nothing until the next five-alarm text. The list crusts over, trust erodes, and each new “EMERGENCY” raises less money and fewer hands.

At its best, mobilizing pairs ruthless focus with a moral frame broad enough to make strangers feel like teammates: the climate-strike students who synchronized walkouts in 150 countries, then hand-wrote welcome texts to every first-time marcher within 24 hours. At its worst, it’s the hashtag that peaks on Monday, vanishes by Wednesday, and leaves local organizers scrambling to explain why nothing actually changed.

WHAT ORGANIZING ACTUALLY DOES

Organizing starts not with a press release but with a power map. Before a single event is scheduled, we interrogate the terrain:

What exact decision must flip, and by when? Who can actually say “yes” or “no,” and who whispers in their ear? What do those actors prize most, votes, profit, reputation, stability, and where is that prize exposed? Which organized people, money, and narrative can we already marshal, or quickly build, to press on that nerve? Finally, what public action will convert our assets into a cost they can’t ignore or a benefit they crave? Those five questions sketch the first draft of any serious campaign plan.

With that x-ray in hand, organizers move outward one conversation at a time, braiding individual self-interest into a shared stake. Over months, sometimes years, those braids stiffen into infrastructure: a tenant union that can jam eviction court, a student coalition that can veto tuition hikes, a neighborhood committee that can rewrite the city budget.

Because the metric is durability, early gains can look modest. A ordinance change, a budget line, a single board seat. Yet each small victory is a proof of concept: we flexed, and power shifted. That visible change lights up recruitment, the fly-wheel turns, and leverage compounds.

Below is the snapshot that keeps me honest when I’m building a campaign plan:

THE FUNCTIONAL FAULT LINE: POWER ANALYSIS VERSUS TURNOUT ARITHMETIC

A campaign’s very first document reveals which engine it’s building.

Organizing opens a power chart. Names, institutions, and the relationships connecting them get pinned like circuitry. The questions are: Who has unilateral authority? Who influences them? What do they fear or need? That map dictates the next six months of one-to-ones, leadership development plans, and steadily escalating structure tests designed to move a small number of decisive people.

Mobilizing opens a turnout model. Districts or precincts are stacked in a spreadsheet, every row tagged with target universes, contact rates, and vote goals. The questions are: Where is our vote margin hiding? How many persuadables can we touch per shift? How many dials, doors, or ads do we need to close the gap before the buzzer sounds?

Both models are essential, yet neither is sufficient alone. Without precise turnout goals, even the most sophisticated power analysis can leave campaigns stranded without enough bodies to move the needle. Without strategic power mapping, even record-breaking voter outreach efforts may fail to secure meaningful and lasting victories. Effective strategists fuse these tools: they know when to rely on turnout arithmetic and when to shift gears to targeted, relationship-driven pressure.

A campaign that neglects power analysis can hit every numeric goal and still fail to secure lasting change because they’ve mistaken numbers for influence. A campaign that overlooks turnout metrics might have flawless intel on their target’s weak spots but remain powerless to exploit them.

The best campaigns start with dual maps: a power map to clarify leverage points and a turnout model to mobilize enough strength at those critical junctures. They coordinate these tools to transform raw energy into targeted power, ensuring that each action—whether a rally, canvass, or digital blitz—builds momentum toward durable structural wins.

In other words, organizing and mobilizing are the complementary engines of successful movements—each has unique roles and responsibilities, and mastering both is the difference between fleeting success and sustainable power.

WHY CONFLATING THE TWO IS KILLING OUR CAPACITY

Grant-report inflation. Philanthropy pays on quarterly metrics, contacts made, impressions served, dollars raised, so progressive nonprofits rebrand every activity as “organizing” to stay competitive. The word’s meaning stretches until it snaps. Line items for slow work, political education, leadership retreats, internal democracy, get trimmed because they can’t hit a weekly KPI. Staff who should be mentoring new leaders spend their Fridays fudging “relational touches” in a database to satisfy a grant portal.

Inflated titles, shallow skills. When "Organizing Director" or "Lead Organizer" titles are handed out to staff whose primary experience is managing email blasts and digital outreach, organizations risk creating a serious skill gap. Resumes might get padded, but critical expertise, like campaign strategy, power mapping, and building leadership structures, is missing. When staff turnover hits or a major crisis emerges, like COVID, Dobbs, or a citywide strike, groups discover they've built impressive contact lists but lack experienced organizers who can design effective campaigns, analyze power dynamics, and mobilize members to take strategic action.

Burnout loops. Mobilizing techniques grafted onto organizing timelines chew up people faster than they can be replaced. Volunteers accustomed to adrenaline hits wonder why they’re now sitting through bylaws debates; core members used to deliberate process resent frantic 48-hour pushes. Everyone feels they’re doing the wrong work on the wrong clock.

Lopsided battlefields. The hard right solved this puzzle long ago. They bankroll multi-decade institutions, think tanks, legal shops, campus networks, and operate outrage machines that can flood a state-house switchboard by noon. Progressives too often respond with either

a six-week text-bank that vanishes at certification

a venerable coalition that never stretches beyond its core, leaving hot fights under-resourced.

Strategic blind spots. Mobilizing without analyzing power dynamics might win an election battle but lose the policy war. You might successfully defeat a harmful ballot initiative only to see legislators rewrite the rules in the next session. On the flip side, having a strong analysis of decision-makers and their pressure points, but lacking the capacity to turn out enough people, can leave you isolated, standing at a press conference with a handful of allies while your opponents pack the room. Unused power fades away; energy without clear direction quickly fizzles out.

As one who joined a phone banking mobilization effort this very evening, I absolutely feel your message resonating with me. During Zoom call outlining the problem and making the call to action, I had a sense of something exciting and important in the works, but also worryingly fragile and desperate, an attemptto make some difference immediately before an urgent deadline hits. I couldn't put my finger on the source if my concerns until I read your piece here.

This is brilliant. Thank you. I’ve been trying to explain the difference to my friends. Now I have something to send them. Funny story about organizing and philanthropy: Back in the late 90s/early 2000s, when I did two non-continuous stints in the communications department at the Ford Foundation, we were not allowed to use the word “organizing” in print. Even if it said that’s what the money was for in the grant. We had to call it “community development.” Laughing, so as not to cry.